Gloria P. Flores

November 02, 2020

Talking to one of my sons recently, he shared that he was frustrated with what he perceived as an emerging closed-mindedness in some of his peers. Lately, he said, a couple of his friends seem to only care about being right, behaving as if their own opinions are the only valid ones. In addition, they are seemingly uninterested in listening to others’ points of view, and sometimes base their opinions on faulty or one-sided information. Instead of listening, they attack the other person’s views, credibility, and/or character.

In addition to being frustrated with his friends, I could tell my son was also a bit sad. “How could friends choose to not even try to listen to each other? Is this why people stop being friends?” It was clear to me that he cares deeply about his friends, but it was also apparent that he is struggling with the way they are engaging in conversations––so much so that it was jeopardizing his relationships.

What my son shared was not unfamiliar to me. It’s probably not unfamiliar to you either. People’s inability to listen to each other, in politics, at work, and even in our families, is widespread. In the work that my colleagues and I do, we often interact with people who say they can’t work with their colleagues, even though they would like to be able to do so. They are often frustrated and resigned about their inability to make things happen, and they don’t feel like they can talk to their colleagues about it. “Why is it always his way or the highway?” “My boss won’t listen to me. She never does.” “I don’t think we are doing the right thing, but I can’t get them to listen to me. Their minds are already made up.”

To be clear, there is nothing wrong with having different opinions, and having different opinions doesn’t mean that you can’t be friends. It also does not mean that you can’t work successfully together. But since we’re bound to have different opinions than our friends and coworkers, we need to learn to listen to each other. How do we begin to do this?

Distinguishing Assessments from Assertions

The late U.S. Senator Patrick Moynihan stated that everyone is entitled to their own opinions, but not to their own facts. The challenge is that many people (including some who like to quote Senator Moynihan) regard their own opinions as if they were unassailable facts, and therefore not up for discussion. By not engaging in conversations in an open, explorative manner, we do a great disservice to ourselves, to our relationships and to our future. Consciously listening to and exploring each other’s assessments has become a critical skill.

My colleagues and I refer to the different evaluative opinions that people have about how things are—and how they should be—as “assessments”; “assertions”, on the other hand, are stated beliefs about the facts of the matter. As a rule of thumb, assertions are backed up by evidence that almost anyone would be able to agree to, just by opening your eyes and looking (i.e. “the chair is blue”), whereas assessments depend on a person’s tastes, personal values, and sense of what is important (i.e. “this chair is perfect for our living room”).

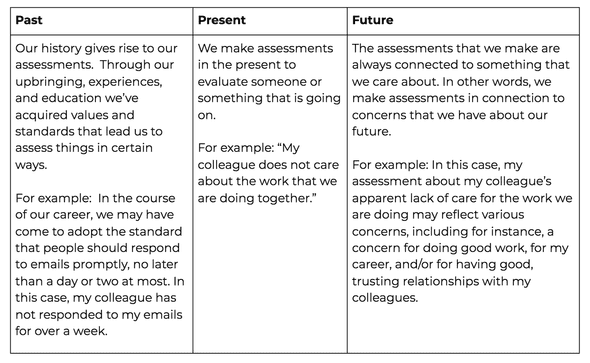

Why is this distinction so important? Because through our assessments, we are saying something about our past, present, and future. A conversation with someone about their assessments, if one is listening carefully, can reveal a great deal about their history, concerns, and aspirations. This kind of information can help us tremendously in building and cultivating our relationships with our friends, coworkers, and clients alike.

A simple table can perhaps better illustrate the information hidden within an assessment:

Facts do support assessments, but even if an assessment is well supported by many compelling facts, the evidence does not mean that the assessment itself is a statement of fact. Two people working together may have very different assessments about what appears to be the same set of facts, and may reach totally different conclusions about the appropriate course of action. Given different histories and concerns, what is important to or appropriate for one person may not be for another.

Exploring Assessments

People don’t always have to agree with each other to find common ground. It is okay to disagree. But disagreeing does not give people an excuse not to listen.

To reiterate - assessments are not facts, but that doesn’t mean that they aren’t important. If we learn to explore them, they can show us what matters to our colleagues and why, and help us to define what we can do together going forward to address mutual concerns. Assessments are particularly valuable when we must complete a complex project that requires the collaboration of many people, or when we care about building strong, lasting relationships with our colleagues or with our friends.

Listening is a skill. Learning to explore our assessments is a crucial aspect of this skill. Like any skill, it takes training and practice to develop it further. Helping people (and teams) develop this skill is one of the most rewarding parts of the work that we do. At a time where many of us have learned to stop listening (even to people we consider to be our friends), developing our ability to do so is one of the best investments we could make in our future.

If you are interested in learning more about Working Effectively in Small Teams, one of our company’s core programs, click here.